Current Season

Presenting the 2023-2024 Season of the

Three amazing concerts at Hutchinson Fox Theatre! This season is filled with incredible music and unforgettable guest artists! Click on Concert below for Tickets or click here for the best deal, Season Tickets!

Dear Patrons and Friends,

We are delighted to present an exciting season line-up and trust that you will greatly enjoy each concert!

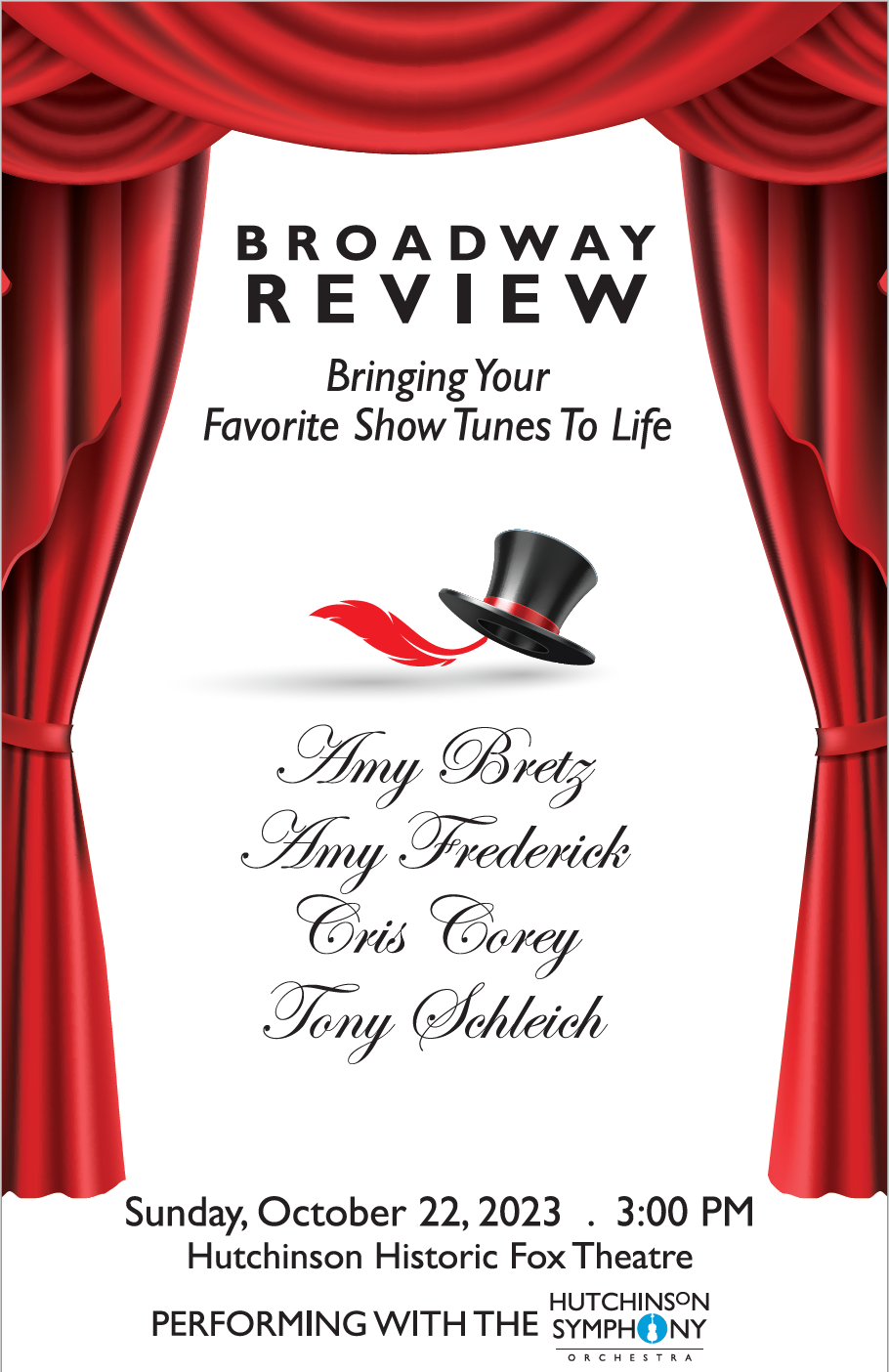

Sunday, October 22nd, 2023

3:00 PM

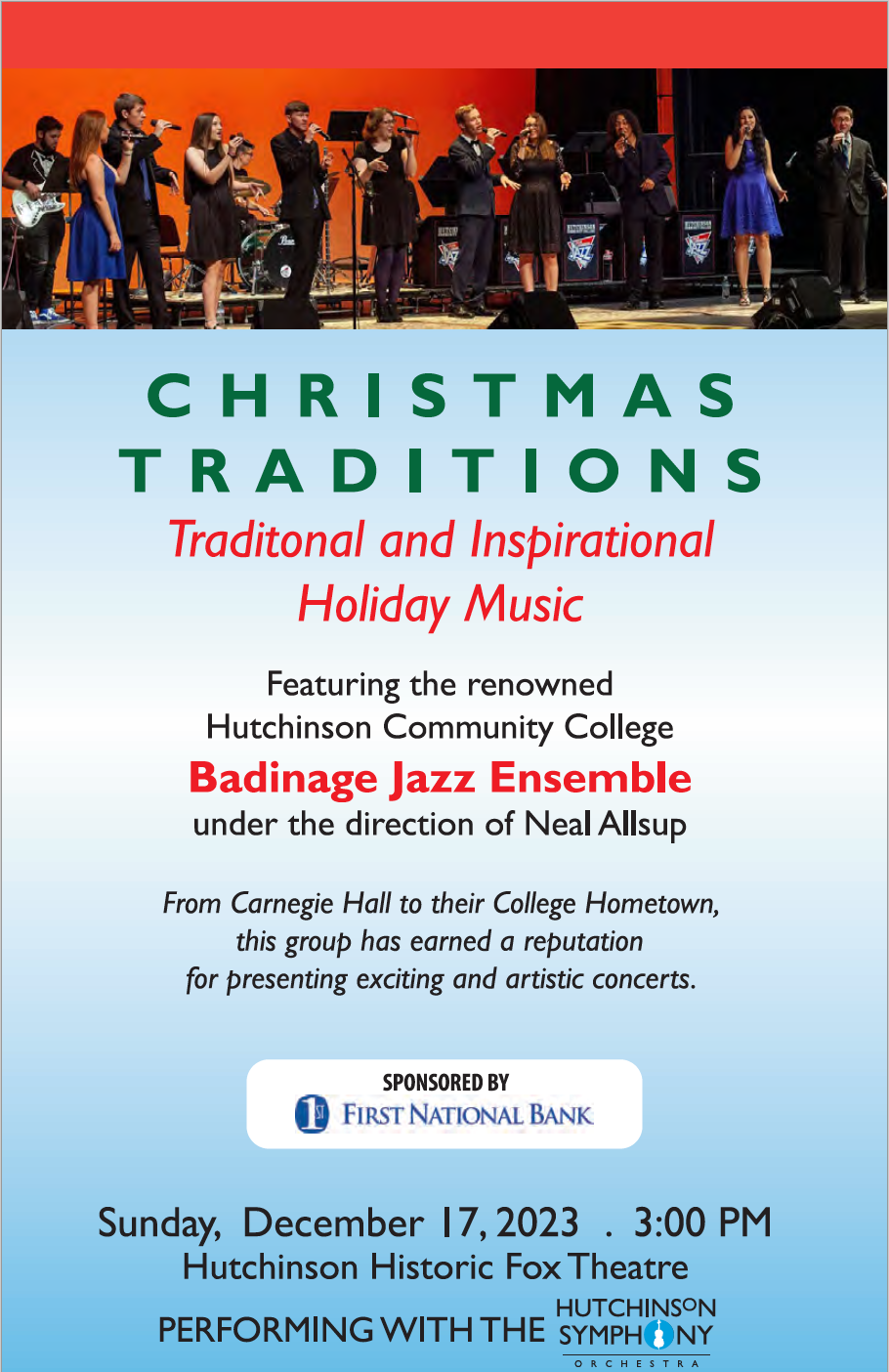

Sunday, December 17th, 2023

3:00 PM

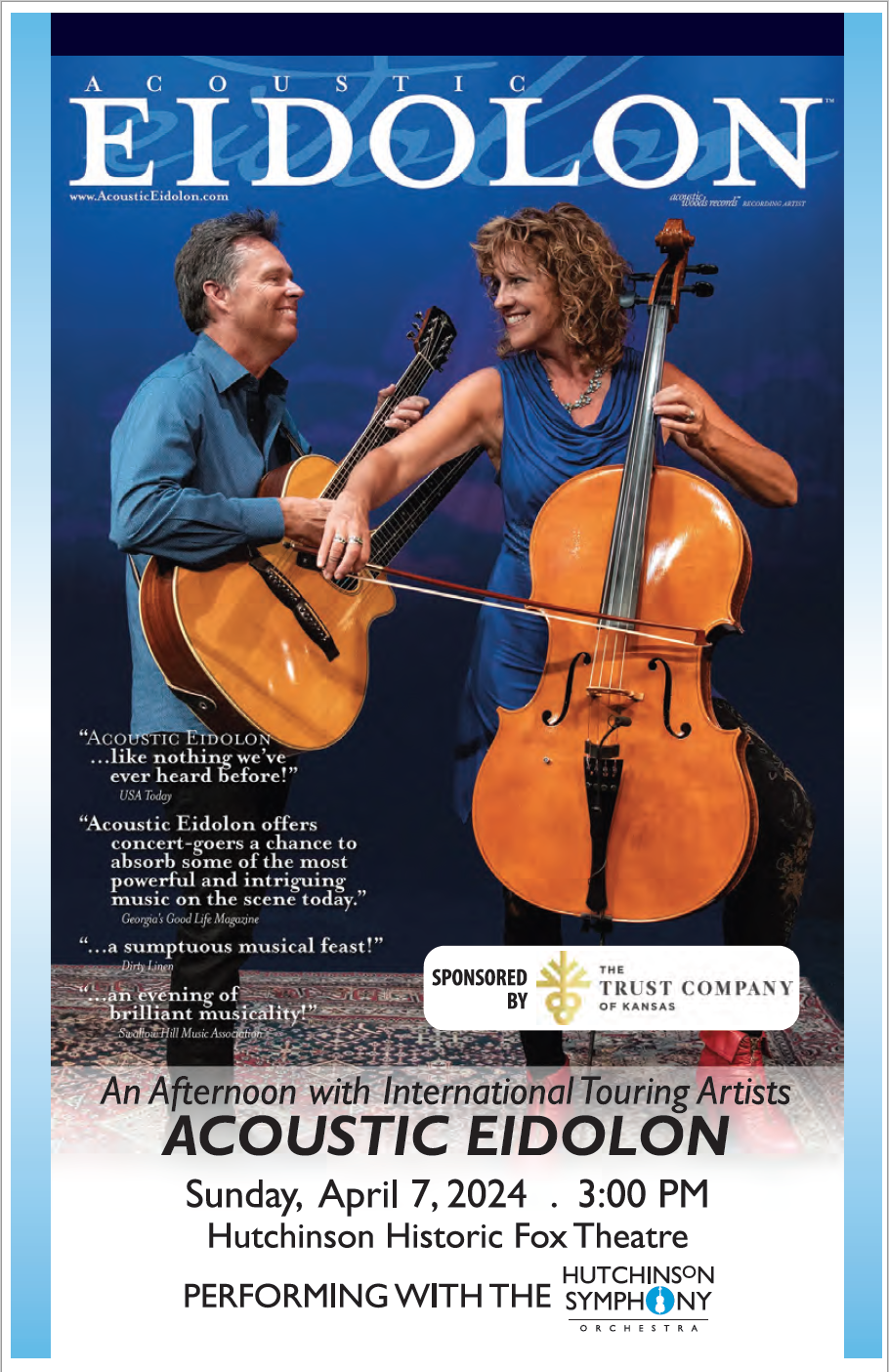

Sunday, April 7th, 2024

3:00 PM

Season tickets are available now at the Fox Theatre, click here

All three Symphony Concerts will be on Sunday afternoons at 3 o’clock at the Hutchinson Historic Fox Theatre. Ticket pricing at $84 for all adults is increased to cover guest artists and increased expenses for the Symphony Association to continue to operate. However, Season Subscribers enjoy a 20% discount over individual ticket prices which are set at $35 per ticket. Your ongoing contributions and sponsorship underwriting is not only deeply appreciated but critical to sustaining the non-profit Hutchinson Symphony Association.

We asked and heard many of you say that you wanted more variety and more vocalists. We will continue to invite your feedback and to listen. Our hope is that you invite a friend and share this gem so that the Orchestra can continue to perform in Hutchinson!

We are also thrilled to welcome Music Director, Dr. Richard Koshgarian back to his important leadership role with the Symphony this season.

Yours truly,

Dianne Blick

Board of Directors

Dianne Blick, President

Kerry Robinson, Treasurer

Jacque Roberts, Secretary

Bruce Boyd

Martha Fee

Dr. Richard Koshgarian, Ex-Officio